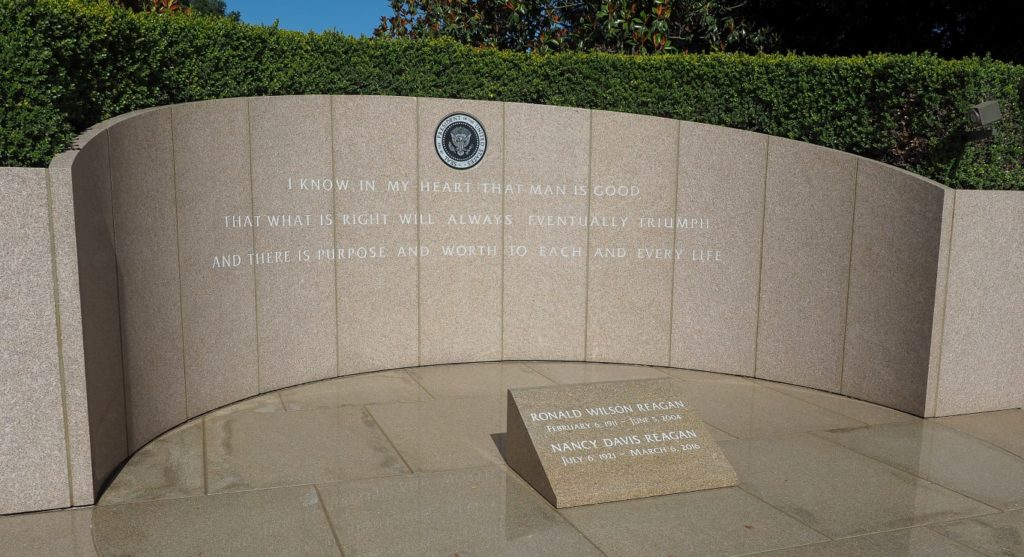

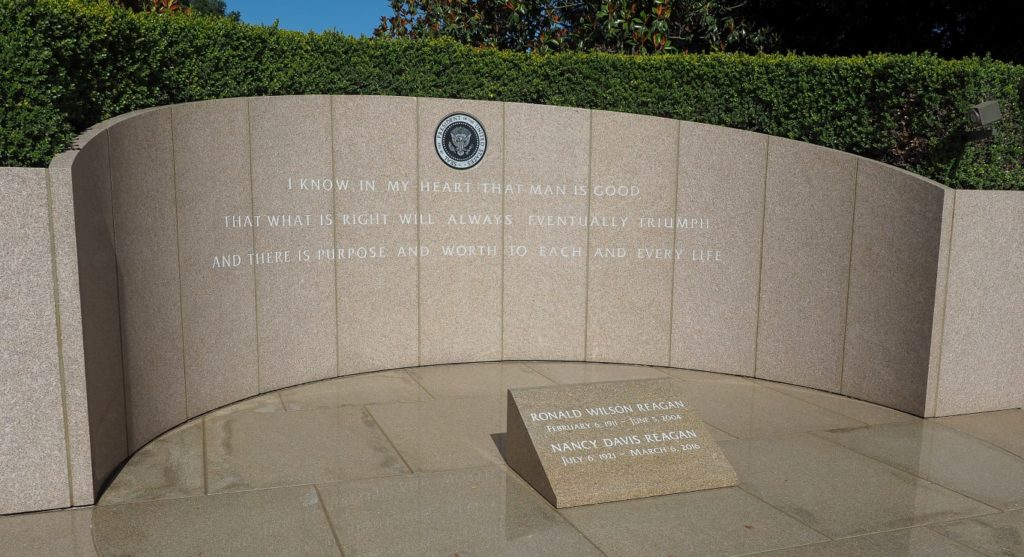

Finding ourselves with an unexpectedly clear afternoon, we decided to bip on over to the Reagan Presidential Library, 60 miles away in Simi Valley, California. What a wonderful and inspiring afternoon.

H. W. Brands, in his recent biography Reagan: The Life, makes the point that there are only two twentieth-century presidents who matter: FDR, for having launched the welfare state and the resulting culture of dependency on government, and Reagan, for having launched the conservative revolution and the resulting aversion to government intrusion on individual and economic freedom. Much of the conflict in current-day politics can be seen as the continuing clash of these two philosophies.

Government is not a solution to our problem; government is the problem.

Government’s first job is to protect us from others; it goes wrong when it tries to protect us from ourselves.

Government is like a baby. An alimentary canal with a big appetite at one end and no sense of responsibility at the other.

No government ever voluntarily reduces itself in size. So, government’s programs, once launched, never disappear. Actually, a government bureau is the nearest thing to eternal life we’ll ever see on this earth.

But the reason Wendy and I found the history of Reagan’s presidency so compelling had less to do with the broad contours of political philosophy and more to do with the stark contrast between the nature of the presidency as it existed just a few decades ago and the way the presidency has manifested itself over the past 10 years. Just a couple examples.

When Reagan took office, the country was in desperate condition on essentially every front. The economy had ground to a halt and inflation had skyrocketed, a combination that liberal economists said was impossible and found themselves forced to invent a new word to describe it: stagflation. After the Vietnam War, Watergate, and Nixon’s resignation, confidence in American government was at an all-time low. In 1975, Saigon had fallen, resulting not only in the expansion of oppressive totalitarian governments into Southeast Asia, but leaving 55,000 Americans seemingly having died for nothing. Radical Muslims were threatening world stability, American diplomats were still being held hostage after a year and a half in captivity, and the failed rescue mission only further compounded the sense of the government’s impotence. The Arab oil embargo had shown the whole country was at the mercy of people who hated us. And to top of off, Jimmy Carter’s famous “malaise” speech in 1979 left Americans feeling like our only option was to blow our own brains out.

Reagan took stock of all this and, incredibly, decided that the solution lie not so much in a patchwork of policies and programs, although he had those ready to go, but in an appeal to American values. “Our problem,” he said, “is that we’ve lost faith in ourselves.”

The greatest leader is not necessarily the one who does the greatest things. He is the one that gets the people to do the greatest things.

Reagan realized, more than any president in my lifetime, and certainly more than the pitiful instances we’ve seen in the past ten years, that the first task of a leader is to inspire people to a common vision.

There are no constraints on the human mind, no walls around the human spirit, no barriers to our progress except those we ourselves erect.

We’re Americans, and we have a rendezvous with destiny. No people who have ever lived on this earth have fought harder, paid a higher price for freedom, or done more to advance the dignity of man than Americans.

A nation’s greatness is measured not just by its gross national product or military power, but by the strength of its devotion to the principles and values that bind its people and define their character.

Above all, we must realize that no arsenal, or no weapon in the arsenals of the world, is so formidable as the will and moral courage of free men and women. It is a weapon our adversaries in today’s world do not have.

In his farewell address eight years later, Reagan summed up what had guided him during his presidency:

I wasn’t a great communicator, but I communicated great things, gathered from our experience, our wisdom, and our belief in principles that have guided us for two centuries.

The change in national psyche was astounding. Within months, Time magazine (Time magazine of all things!) pronounced in a cover story that Americans had begun to feel good about themselves. Reagan’s views resonated across party lines. “Reagan Democrats,” a newly coined characterization, led him to two landslide victories, including a reelection where he won 49 of 50 states (missing only on Mondale’s own Minnesota, although not by much). His firing of 11,000 air traffic controllers who illegally walked off their jobs further solidified the change in national disposition that we would not be held hostage by anyone ever again, not externally or internally. We were confident, energetic, and optimistic.

The second aspect of Reagan’s presidency that inspired us was they way he dealt with the Soviet Union. During the 1960s and 1970s, the Soviets had pulled a rope-a-dope on America, persuading us to buy into “detente,” while they engaged in a massive military buildup and we depleted our military, both in personnel and materiel. As a result of Carter Administration policies, the American military was plagued by low morale, low pay, outdated equipment, and practically zero maintenance on what did exist. Reagan knew as well as anyone that, even though the effort would be expensive and, in a way, contrary to his goal of controlling federal spending, to defeat communism, he had to begin by strengthening our military forces. Reagan restored the B-1 bomber project that Carter had cancelled, and when the Soviets deployed SS-20 missiles to Eastern Europe, Reagan responded with deployment of American Pershing II missiles. By the end of his presidency, Reagan had expanded the U.S. military budget to a staggering 43% increase over the total expenditure during the height of the Vietnam war. That meant the increase of tens of thousands of troops, along with more weapons and equipment.

Here’s my strategy on the Cold War: we win, they lose.

The dustbin of history is littered with remains of those countries that relied on diplomacy to secure their freedom. We must never forget that it is our military, industrial and economic strength that offers the best guarantee of peace for America in times of danger.

A truly successful army is one that because of its strength and ability and dedication will not be called upon to fight, for no one will dare to provoke it.

But more than this, Reagan was successful in defeating communism because, unlike the presidents before him, he realized that American didn’t have to take on the destruction of communism. Communism was inherently unstable and unsustainable. Given the right pressures, it would destroy itself.

The years ahead will be great ones for our country, for the cause of freedom and the spread of civilization. The West will not contain Communism, it will transcend Communism. We will not bother to denounce it, we’ll dismiss it as a sad, bizarre chapter in human history whose last pages are even now being written.

I believe this because the source of our strength in the quest for human freedom is not material, but spiritual. And because it knows no limitation, it must terrify and ultimately triumph over those who would enslave their fellow men.

Therefore, Reagan launched a relentless, uncompromising, focused effort to subject the Soviet Union to economic, military, and moral pressures that they could never withstand. He simply wore them down on all fronts.

The great dynamic success of capitalism had given us a powerful weapon in our battle against Communism–money.

As for the enemies of freedom, those who are potential adversaries, they will be reminded that peace is the highest aspiration of the American people. We will negotiate for it, sacrifice for it; we will not surrender for it, now or ever.

In an ironic sense Karl Marx was right. We are witnessing today a great revolutionary crisis, a crisis where the demands of the economic order are conflicting directly with those of the political order. But the crisis is happening not in the free, non-Marxist West but in the home of Marxism- Leninism, the Soviet Union. It is the Soviet Union that runs against the tide of history by denying human freedom and human dignity to its citizens.

The Soviet Union is an Evil Empire, and Soviet communism is the focus of evil in the modern world.

Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.

This post is already too long, and I could go on forever. But one more point. Part of Reagan’s success in defeating communism can be traced to his relationship with Mikhail Gorbachev, a relationship that adversarial, to be sure, but which was also built on trust and, ultimately, friendship. The museum recounts the famous story, but it’s worth retelling. In preparing for his summit meeting with Gorbachev, Reagan’s advisors were warning him that Gorbachev was a tough cookie, hard, focused, uncompromising, and humorless. “Maybe I should tell him a joke,” Reagan suggested. “No!” the advisors cautioned. “Do not under any circumstances tell Gorbachev a joke.” So what did Reagan do? Started his summit meeting with this:

Mr. Gorbachev, I heard that a Russian citizen went into the local KGB office to tell them that his parrot was missing. “That’s not our business,” the KGB officer responded, “tell it to the local police.” “I know I have to tell it to the local police,” the man responded. “I just want the KGB to know that I disagree with everything that parrot says.”

Gorbachev paused for a moment, and then burst out laughing.

Wendy and I, like I expect most Americans, are worn down by the politics of the past decade, how the political parties have been captured by the lunatic fringes of their constituencies, and do little nowadays other than spew rancor and hatred, bent on each other’s destruction, happy to take the country down in the process. Spending the afternoon in the company of a man who inspired a nation and changed the world buoyed our spirits and inspired our hopes. Americans are great people, and America really is a beacon to the world. Reagan knew it, and maybe someday will have a leader who unites America in remembering it.

At left: The General Sherman Tree (Southerners… don’t freak out. After all, they did win, so they get to name the trees.) The General Sherman Tree is considered to be the largest tree in the world, although “only” 275 feet tall (there’s a coastal redwood that’s 380 feet tall), and “only” 2300-2700 years old (there’s a Bristlecone pine that is slightly more than 5000 years old). But its volume is an incredible 52,000 cubic feet, equivalent to 7.5

At left: The General Sherman Tree (Southerners… don’t freak out. After all, they did win, so they get to name the trees.) The General Sherman Tree is considered to be the largest tree in the world, although “only” 275 feet tall (there’s a coastal redwood that’s 380 feet tall), and “only” 2300-2700 years old (there’s a Bristlecone pine that is slightly more than 5000 years old). But its volume is an incredible 52,000 cubic feet, equivalent to 7.5