Cody was something of a deviation from our national park-based itinerary, but a stop that was high on our priority list, mainly because in all of our conversations with fellow RVers, as soon as the word “Cody” was mentioned, it seems like everyone immediately said, “You’ve got to go to the museums in Cody.” Frankly, it got to be a little weird. Sometimes we weren’t even talking about Cody, just maybe something about shortcutting across Wyoming, and the comment was the same: “You’ve got to go to the museums in Cody.” What the heck, over?

As it turns out, the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody is worth every accolade it receives, a “gem” as the AAA Tour Guide puts it. There are actually five world-class (like Smithsonian quality) museums here: the Buffalo Bill Cody Museum itself, the Draper Natural History Museum, the Whitney Western Art Museum, the Cody Firearms Museum, and a Museum of the Plains Indians. Each is, in its own way, memorable. The firearms museum, for example, houses the largest collection of firearms in the United States, and the second largest in the entire world. (Only the Ruskies have one that’s bigger.) We attended a lecture on the firearms of the old west, starting with the flintlocks used by the early trappers and continuing through the Colt Peacemaker and Winchester 73. All of the firearms were in working order and available for people to handle. Fascinating. The museum of western art houses an extensive collection, organized along various themes (landscapes, animals, people), including a whole wing dedicated to art depicting the sights of Yellowstone. It has extensive collections of works by Remington and Russell, and even has a full-size replica of Remington’s studio in New Rochelle, NY. As we were walking around, there was a lecture comparing Paxson’s famous “Custer’s Last Stand” to a contrasting Indian painting depicting the same battle (both part of the museum’s collection). Although I’m not generally very interested in American Indians, the Museum of the Plains Indian provided extensive displays, films, and audios showing traditional Indian life (both before and after the arrival of horses), Indian encounters with the white man, and Indian life since then. The natural history museum, besides providing wonderful displays of the wildlife of the Yellowstone ecosystem, features a huge wing built using a series of circular ramps and staircases, allowing visitors to work their way downward through the various zones of the western ecosystems, starting with the alpine environment (above 10,000 feet), and working down to the subterranean layers where fossils and natural resources tell the story of prehistoric times.

In addition to the permanent displays, there are always fascinating temporary exhibits and lectures. Currently, there’s one on gunfighters of the old west, a display I really, really wanted to see, but forgot about and missed because I have no brain.

I regret that this little blurb really can’t do justice to the true excellence of this museum complex, but if you’re sitting around, just page through the museum’s web site and get a sense for yourself.

Given all of this, one might ask how it could be that museums of such conspicuous quality could come to be located in, of all places (no offense intended), Cody, Wyoming. We asked. The answer is that it all began with Buffalo Bill Cody himself, who used the money he made from his Wild West shows to found, organize, and develop the town of Cody. Then, starting with the original museum of Buffalo Bill memorabilia, a long list of benefactors (including, of course, Laurance S. Rockefeller) began expanding the original structure and donating items for the collection. Over time, the momentum of it all created something of a chain reaction that ended up with world-class displays in multiple areas of focus. It has now gotten to the point where about ten percent of each area’s displays are changed out each year, and each museum’s entire display is actually replaced every 10 years. Only about one-third of the collection is on display at any given time. Some of the materials are housed in a special research facility that, unfortunately, will probably never be put on public display. Cody has something to offer hard to find anywhere else.

As if that isn’t enough, Cody is chock full of other “gems.” The Cody Cattle Company dinner and western music show was great. Just to illustrate how good it was, the guitarist is a recent winner of the Western Music Association “Best Instrumentalist” award. And he deserves it. His guitar playing was among the best I’ve ever heard. The music was great (we didn’t want the show to end), the performers were funny and entertaining, and the food was wonderful.

And then it was off to the Cody Stampede Rodeo. I love rodeos. You might think that a rodeo that performs every night in the same place wouldn’t be up to the standard of rodeos one would see on the circuit, but it was darn good. Most of the performers are PRCA cowboys, working during the summer to “put food on the table” (as the announcer put it, implying, without saying as much, that being a rodeo cowboy is a hard life), and the rest of the performers were very competent locals, including a bunch of youngsters (even young bronco busters) that made for a completely wonderful show.

And the next day, it was another “gem”: Old Trail Town, a collection of actual buildings from the old west that have been carefully relocated to Cody, including for example the cabin used by Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid as they hid out after their exploits. And a bunch of famous old west personalities are buried here, including Jeremiah Johnson.

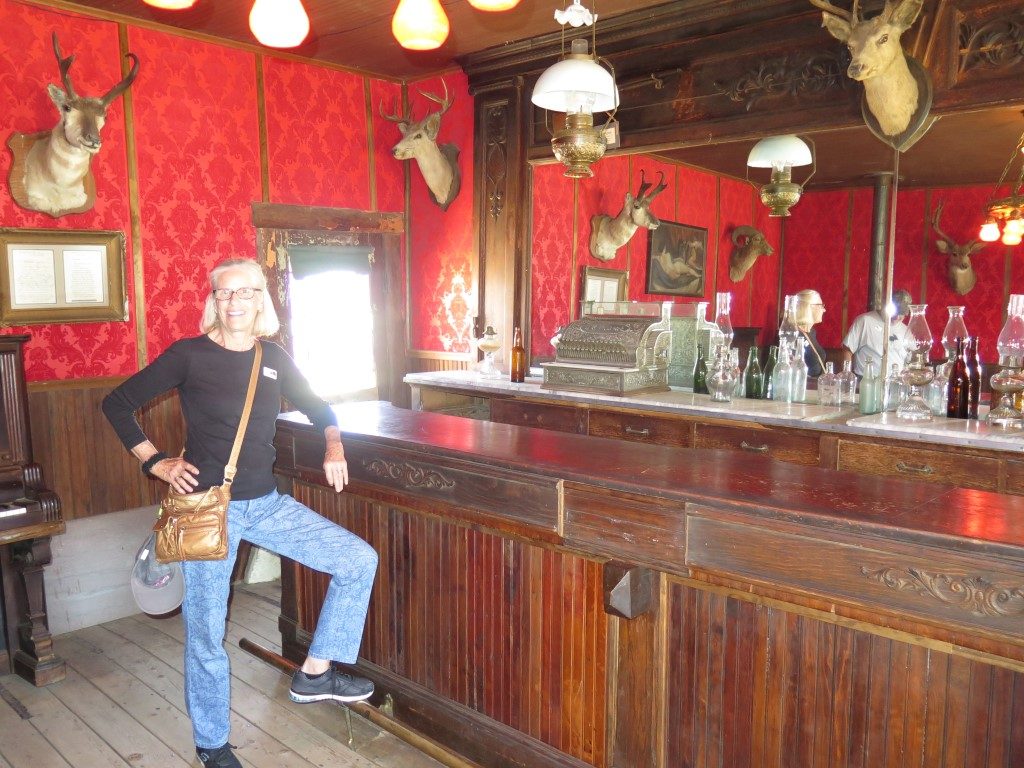

I know this is getting repetitive, but there was yet one more “gem” on the itinerary: the Irma Hotel, the hotel build by Buffalo Bill himself and named after his daughter, Irma, and famous for its $100,000 bar. We treated ourselves to an all-you-can-eat prime rib dinner that was wonderful.

And, of course, all good saloons come with a, um, what did they call Miss Kitty, a “hostess”?

So Cody was a great stop in all respects and a fitting finale. Our trip of a lifetime is basically over, and today we start the L-O-N-G trek home. Some final thoughts about the trip, and the prospects for the dogs, will follow once we’re back.