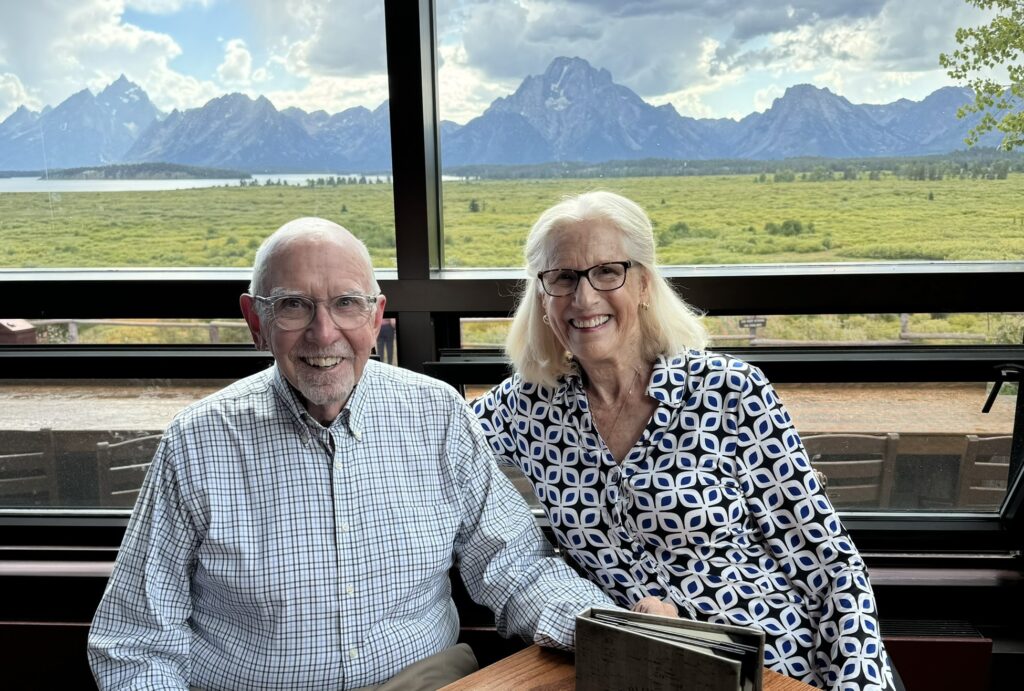

As we were driving in to Grand Teton National Park and getting our first views of the Teton Range in the distance, we both looked at each other and said, no kidding, “We’re home.” That pretty much sums up this visit.

What precipitated that reaction was the drama that the Tetons present every time one first sees them. Although technically part of the Rocky Mountains, the Teton Range is much younger than the Rockies (10 million years versus 70 million) and gets its dramatic appearance from a unique geological situation: there’s a fault line that runs along the base of the range, and every few thousand years, there’s some seismic shift and the mountains get pushed up five to ten feet, the valley floor hinges down twenty to thirty feet, and presto-change-o, the mountains grow by 40-50 feet and loom even larger. Do that thousands of times and you get this:

It’s just impossible to tire of this view. After half a dozen visits, and countless hours spent taking in this scene, as we are driving around the park we still stop at nearly every turn out and just stare at the vista. It’s irresistible.

The other reasons this place is so compelling is the story behind it. The park itself was established in 1929, but included only the Teton Range. Commissioner Horace Albright quickly realized that the valley at the base of the range would quickly become overrun by commercial interests. So in 1930 he went to John D. Rockefeller and said something like, “I know you’ve already done so much for public lands, but if you could purchase some land here, we could preserve it forever.” Rockefeller agreed and asked Albright to put together a plan. Albright came up with a proposal that was about as much as he thought he could possibly ask for and came back, hat in hand, and said, “I know this is a lot to ask, but if there’s any way you could do this …” To which Rockefeller responded, “Mr. Albright, you misunderstood. I want to know how much it would cost to buy the entire valley.” By 1943, much of the Jackson Hole valley had been purchased and donated to the public and became the Jackson Hole National Monument. In 1950, the national monument was abolished and the land transferred to Grand Teton National Park.

And, as Albright feared, the area of Jackson Hole outside of the park, like the town of Jackson itself, became a pit of vulgar commercialism and exorbitant development. According to a recent Wall Street Journal article, the median price of a home in Jackson is now $4.5 million. But the 310,000 acres of Grand Teton remain now just as they were in the 1930s, and an invaluable gift to the American people.

As usual, there’s so much to do and see in the park that we always seem to find something we’ve never done before. As one example, rangers from the Jenny Lake Ranger Station conduct daily guided hikes to nearby Moose Lakes. Surprisingly, we’d never hiked to Moose Lakes before. What does one see at Moose Lakes?

At one point, the cow moose swam off leaving the young calf on his own. When we asked the ranger if the calf was in danger, he explained that a full-grown moose can run at 40 mph and pretty much stomp to death anything that gets near the calf, including bears and stupid tourists.

We did take a day to drive up to Yellowstone. The bison, of course, clogged up traffic in the Hayden Valley:

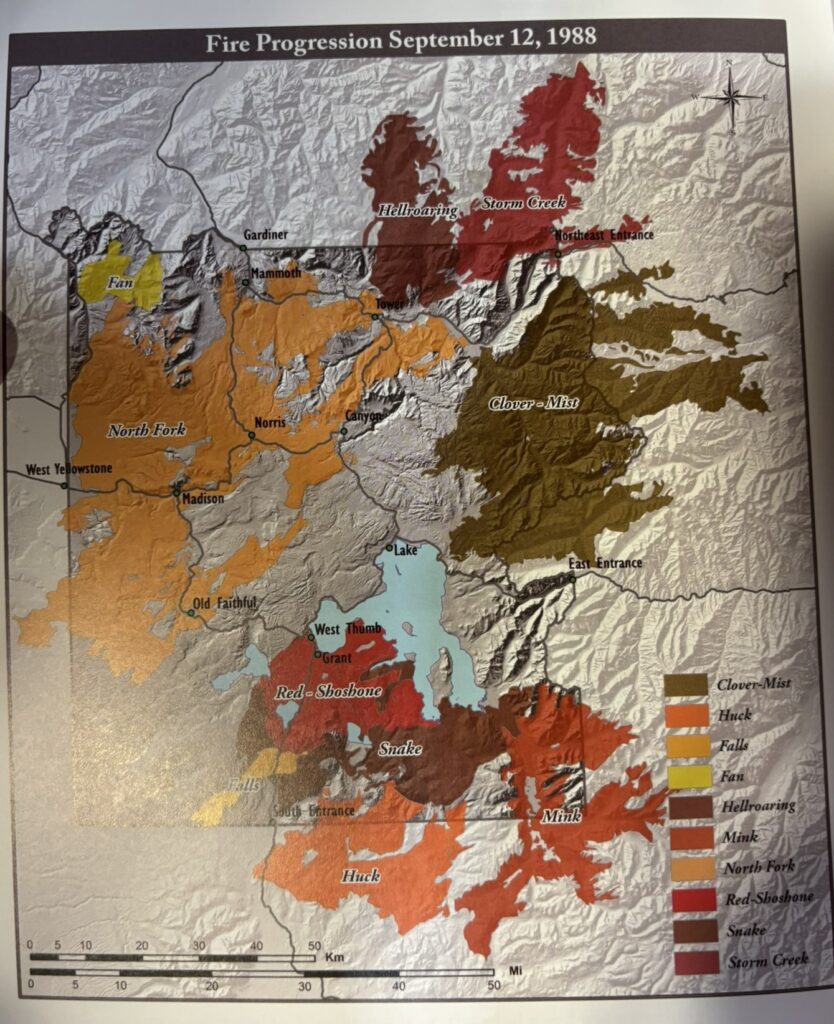

And we spent several fascinating hours studying displays on the 1988 fires, “the year that Yellowstone burned.” We were there that summer, but even though we could plainly see fires burning seemingly everywhere, we failed to appreciate the extent of the burn until we spent time at this exhibit.

Part of the reason for the extensive damage was that the Park Service, along with most federal and state agencies, had followed a practice of suppressing small fires. The effect of that was a buildup of a hundred years of fuel, so when the fires started, it was a well-fed conflagration. The Park Service now recognizes that small fires are part of a natural, healthy forest and allows smaller fires to burn themselves out, especially in remote areas, and actively fights fires only as necessary. Even still, 36 years after we were there in 1988, fire damage is still readily apparent. According to the rangers, it will take roughly 100 years for the forest to recover to the point like it was.

Another half-day trip took us down to the National Elk Refuge, just north of Jackson. No elk (they’re up at higher altitudes during the summer), but during the winter there will be 5000 elk, plus bison, plus pronghorn antelope, on the refuge, but many more in the surrounding areas. I did offer to bring my rifle out and help solve the “elk problem.” There actually are managed hunts on the reserve, with spots allocated by lottery.

And otherwise, it was just hiking, sightseeing, and enjoying the unspeakable beauty of the national park. We’re already planning another trip out west, and of course it will include days in Grand Teton.