I guess “post mortem” isn’t exactly the right term, since technically we’re not dead (yet), but it’ll do.

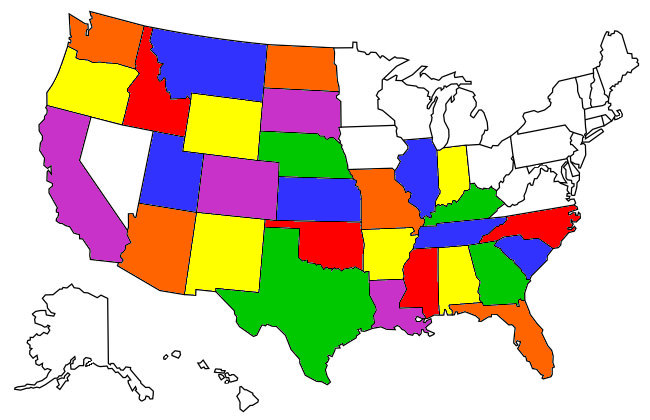

Our trip this year covered 6500 miles in 32 days, through 19 states and 6 national parks. Of the 44 national parks in the continental U.S., we’ve taken our little ACE to 28 of them. Our goal was to spend retirement traveling the width and breadth of the U.S., seeing what the country has to offer, and we’re well on our way to doing that.

The highlight of this year’s summer trip was, of course, the 8-day stretch in the middle with Robert, Laura, and The Boys.

And the highlight of the highlight was definitely the stop at Redwood National Park.

There are lots of reasons why the stretch in the middle of the trip with the west coast fraction of the family was special. Obviously, and firstly, they’re family, and we don’t get to see them as often as we’d like, and they’re the only branch of the family tree with a cohort of little boys, with all that such entails. But beyond that, seeing them on a camping excursion is doubly special. There’s a Ken Burns series on the national parks called “America’s Greatest Idea,” and during the course of that series there are interviews with numerous leading conservationists, among whom there is a uniform and recurrent theme: “I developed my love of nature and my approach to caring for and protecting the natural order over years of camping with my parents.” It is true: Learning about nature by watching the Discovery channel gives one only a superficial and incomplete understanding of the natural world; camping in it adds another level; camping in it in the presence of parents like Robert and Laura adds even more, mainly because they infuse the process with experiences, such as their mandatory participation in the “Junior Ranger” program, that are fundamentally transforming, even (or maybe especially) for little boys. It was a special privilege to be a part of all that.

And, of course, there was our stop in California to see Kathy and Tommy.

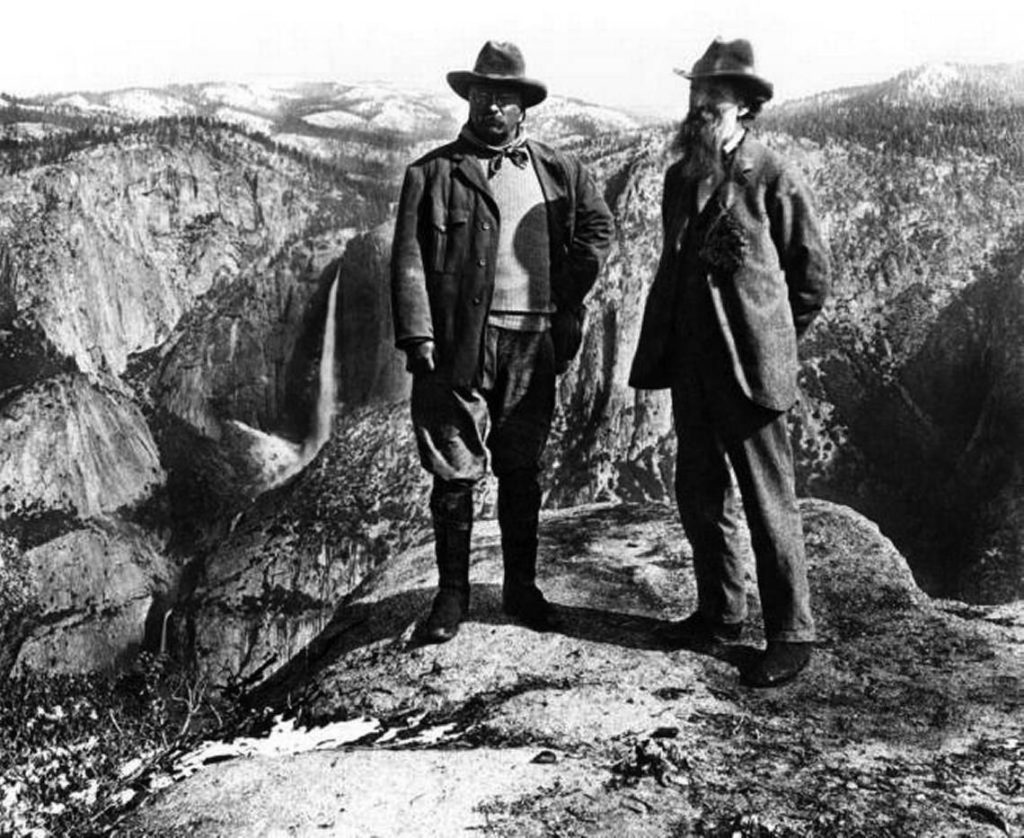

Add the stays at Crater Lake and Theodore Roosevelt national parks, and this trip, despite the challenges (described below), was in my estimation worth every bit of the effort.

However, Wendy tells me that I have PAINTED too rosy a picture of this trip, and she’ll give me a good SHELLACKING if I don’t provide the UNVARNISHED truth. (Enough of that.) So here goes…

For lots of reasons, the planning and execution of this trip was not one of my better efforts. We spent way too many days doing only overnight stops. Spending all day on the road, usually on nothing but interstates, only to stop at some unattractive RV park, set up, eat, crash, pack up, and head out, for days at a time, is just plain brutal, no matter how worthwhile the destination. Plus, on both sides of the family time in the middle, we were confronted with record-breaking heat waves, which pushed the experience from tedious to outright awful. Even our stops at the national parks were too short, just a couple days each, meaning that we were rushed at each location, not even having time to spend an extra few days at each park hiking and exploring. And we ended up racing through some areas, like Montana, where we otherwise would have stopped. The bottom line is that doing this trip in only 5 weeks was a mistake.

How much of the LUSTER (sorry) (now I’ll really stop) this takes off the experience is something that requires some time to work out. My hunch (or maybe my disposition) is that the unpleasant aspects of the trip will fade from memory, leaving only the SHINE (sorry) (I promise, that’s it) of the highlights.