Mt. Rushmore, as a scenic view, is so well known that, although we took approximately one hundred photographs, none of them, except for our presence in the images, show anything not seen countless times before. What photographs do not show, though, is the reason that Mt. Rushmore even exists, something I guess I had never really paused to consider. Unlike other national monuments that exist to preserve physical beauty, or as a refuge for wild animals, Mt. Rushmore exists not to restrain certain human tendencies but to celebrate and encourage certain human tendencies. Mt. Rushmore’s mission is patriotism, but not in some simplistic form of nationalism. It is based on the concept that there really is something unique about American ideals, and Mt. Rushmore depicts four presidents each of whom, in ways that are different but complementary, assured the success of a grand American experiment. It is, in essence, American exceptionalism carved into stone.

Through dozens of exhibits and lectures, this theme emerges. The connection of Washington and Jefferson to American ideals is obvious. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights…,” and that governments derive legitimacy only by “consent of the governed,” were radical views then and probably only slightly less radical now. Catherine Drinker Bowen’s Miracle At Philadelphia made a point that has never left me: the American revolution was the only revolution in history instituted not by the “have-nots” but by the “haves,” privileged people who had everything to lose and nothing to gain except fidelity to what they viewed as a moral duty to pledge their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor to philosophical principles.

The exhibits at Mt. Rushmore also make the point that Jefferson actually gets double credit, adding to his role in the founding of the country the accomplishment of doubling the size of the country by one stroke of the pen, expressing his commitment that the American experiment would apply not just in lands originally signing on in 1789, but by projection to everywhere that American influence could come to bear.

Lincoln’s entitlement to presence on Mt. Rushmore is also self-evident. The Mt. Rushmore message is plain: whatever differences we may have, we cannot and will not ever tolerate deviation from our founding ideals, and that our unity on those points, the unity of our Union, trumps contrary views, no matter how sincerely (or lawfully) held. Lines from the Gettysburg address abound at Mt. Rushmore, conveying the theme that as to people who die in pursuit of American ideals, “these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Teddy Roosevelt’s entitlement was less clear to me, so upon arrival I asked the ranger. What he told me, and then what we saw again and again in the exhibits and displays, is that Roosevelt embodied that idea that American ideals would survive only if manifested in action. Everything that Roosevelt did, from the “trust busting,” to the expansion of American military power, to the brokering of peace accords, and even conservation of precious national resources, was based on his view that ideals are too fragile, too easily lost in the pressures of unrestrained commerce and other forces, to be left to carry on only in the abstract. The essential democratic nature of national parks, for example, was not just a few spectacular vistas; there needed to be tangible preservation in thousands of instances (230 million acres to be precise) making it plain this is our country, our land, and we, the people, own it for our benefit and the benefit of our children.

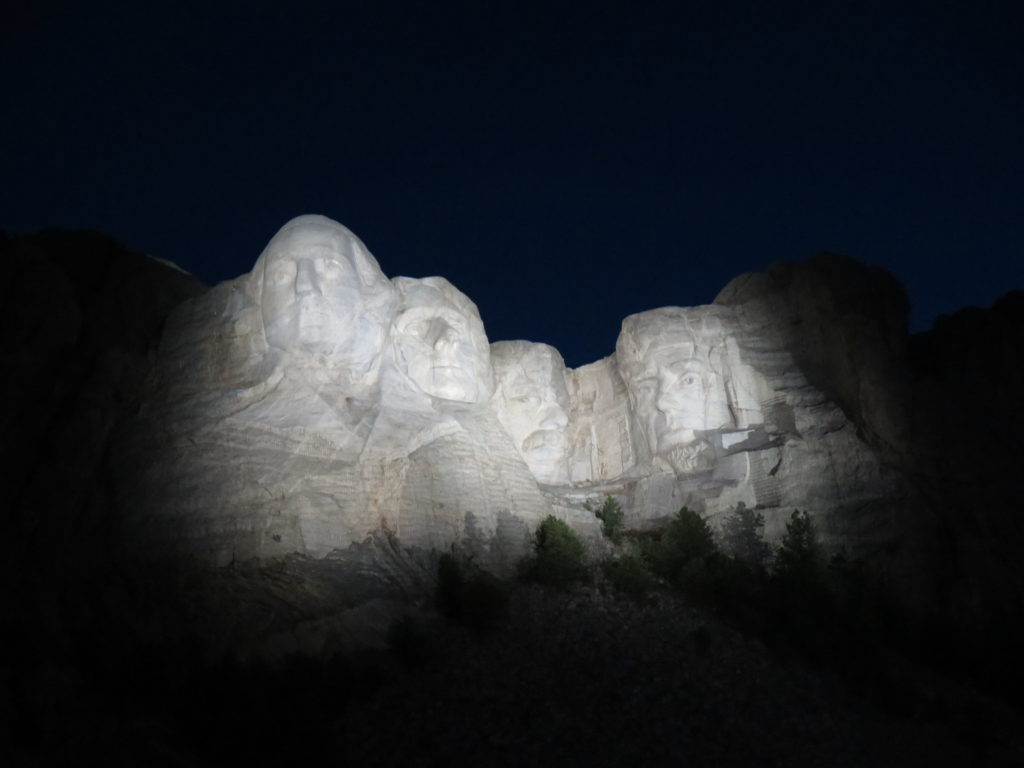

Over and over again, these themes came through. But it wasn’t just the exhibits and displays. One more thing. Every night, there is an “illumination ceremony,” where there is a powerful symbol: in the stark blackness of the universe, while “American the Beautiful” plays in the background, a light shines suddenly on the men who created, preserved, and assured the success of the American ideals.

At the conclusion of that, all members of the military, active and veterans, are invited to come down to the stage for the lowering of the flag. The ranger, a former Marine, announces to the audience, “Ladies and Gentlemen, these men and women were willing to put their lives on the line for the sake of American ideals expressed by these presidents, and we should honor them for that now.” The entire audience applauded, really, as the a few dozen veterans made their way to the stage, and after the colors were retired, each veteran was introduced to the audience by name, branch, and rank.

Wendy made an important point. During the entire evening ceremony, all of the audience was attentive and respectful, even the teenagers. She noted that most of the young people could probably tell you something about Washington and Lincoln, maybe a few would have something to say about Jefferson, and it’s likely that not many could say anything about Teddy Roosevelt. Still, they sat there, absorbing all of this (even if dragged their by their parents), the message recurring, over and over. It has often been said that American ideals are always within one generation of disappearing, but after experiencing Mt. Rushmore, it is easy to be confident that in the future, those who were here will hear an echo of the Mt. Rushmore experience, and in that faint recollection will do whatever it takes to assure the essential American character will never “perish from this earth.”