This is our third trip to the Kennedy Space Center (one in 2015, noted here, and one in 2017, noted here). It had been long enough since our last visit, though, that we decided our memories could use a boost, so we took two days for this visit, which was definitely the right call.

For those of us who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s, it’s easy to be a total, whacked-out, loony space nut. It all started for us when the Ruskies launched Sputnik, which led all of us to keep an eye on the sky lest nuclear bombs start raining down from the heavens. And then President Kennedy announced that we were going to put a man on the moon before the end of the decade, which led all of us to see our national destiny as tied to a lunar landing. So, basically, the whole country went crazy with rockets. Heck, we were so rocket crazy that even our cars had fins!

So, a visit to Kennedy Space Center is in many ways something like coming home. It’s all the stuff that we grew up with, and it’s also everything we’ve seen since then, and all the things we hope to see before we kick the big bucket in the sky. And this trip was worth it on all counts.

First, we took the super-duper, pay-extra, two-hour bus tour of the launch facility, which was doubly worth it in that our guide spent 40 years as a NASA engineer and Mission Specialist and was as close as one can imagine to a human incarnation of Google. We heard later that he has something of a reputation among the other guides because his narration is so fact-filled that many tourists find their eyes rolling back in their heads, but for those like us who want those kinds of fact-filled narrations, keep our eyes in the unrolled position was easy. And then, as it turned out, the very same guide was conducting the guided tour of the Atlantis space shuttle exhibit, so we jumped in on that as well.

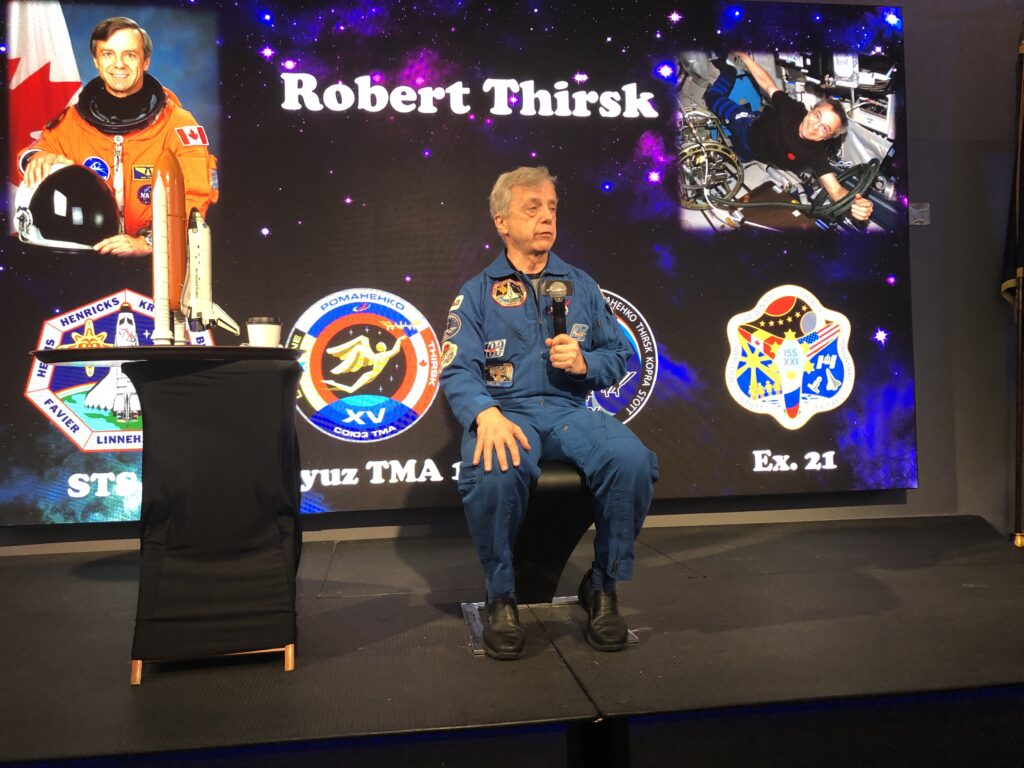

Second, we did the super-duper, pay-extra “breakfast with an astronaut,” in this case Bob Thirsk, a Canadian engineer and medical doctor who did two trips to space, including a 180-day stint on the the International Space Station. And not only did Dr. Thirsk give us a wonderful, hour-long opportunity to ask questions and get to know him personally, he then conducted an hour-long lecture on what it’s like to blast off into space, spend six months in space, and then return.

Finally, we got to spend a lot of time in KSC’s “exploring Mars” exhibits. A few years ago, we went to the “Biosphere 2” facility in Tucson. You may recall, the original BIosphere was an attempt back in 1991 to seal up eight people in a huge, self-contained structure where they would live for two years, producing their own food, using plants to produce oxygen, recycling waste to grow the plants, blah blah blah. It was sort of like the grown-up version of those terrariums you made as a kid with the plants, the puddle of water, and a little frog (that promptly died and got dried out and your mom told you to get that stinking jar out of the house). That Biosphere experiment had basically the same outcome (mainly because, among other things, they ran out of oxygen) (oops).

Anyway, as we were touring the facility, I kept thinking, “This place would be great if we could build it on Mars!”

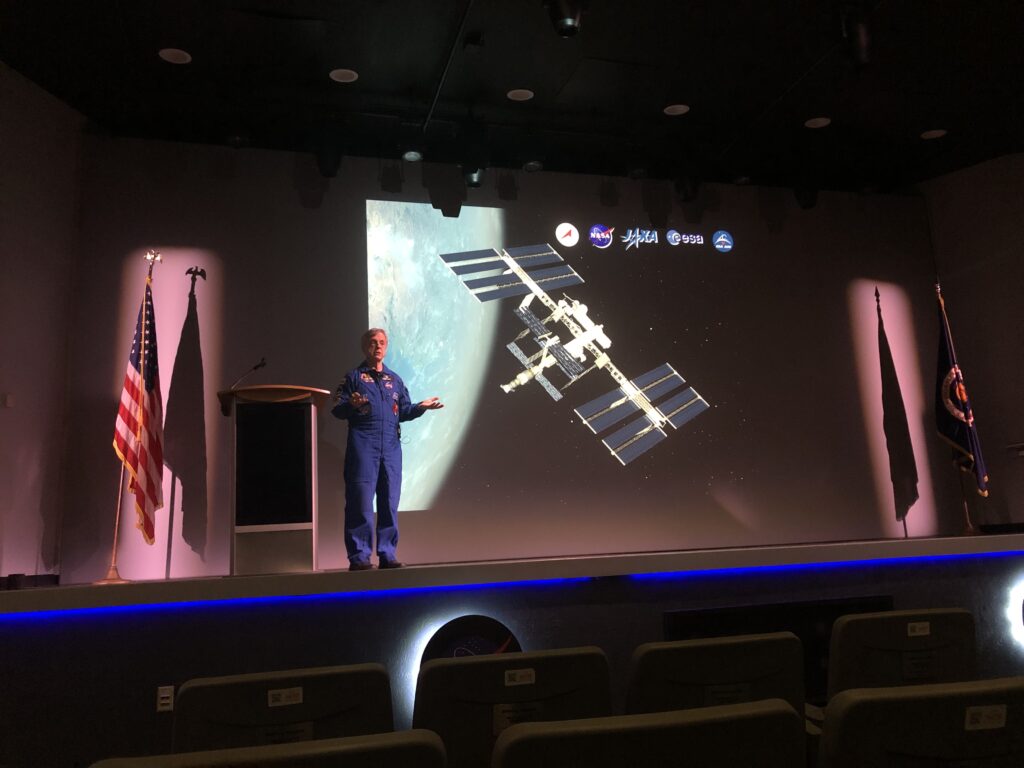

That’s what a large part of the KSC Mars exhibit is all about. In 2020, scientists identified 14 technical hurdles that must be overcome for man to successfully travel to and from Mars. The most interesting ones revolve around the fact that the mission would take roughly 3 years each way, and there’s no way to stockpile enough food for a mission of that duration. Therefore, there has to be a way to grow (!) food for the mission. Combine this with the effects of microgravity over such a long period, shielding from ionizing radiation, and the absence of technology sufficient for propulsion and power for such a mission, and one might think that the challenges are insurmountable. Well, when Kennedy announced we were going to the moon, Americans had spent a total of 16 minutes in space. In that same way, just because going to Mars seems impossible now doesn’t mean we won’t be walking around on the Red Planet in a few years. The current plan is to be there by the late 2030s. I hope I live long enough to see it.

There’s one other thing to say about all this, but I’ll make it a subject for the next post. As a preview, though, NASA fully realizes that to move into the next phase of space exploration requires two things: a zeal for exploration, and a nation committed to scientific and engineering excellence, both of which, given a wide range of factors, are considerable challenges. More to follow …