We’re depleted. We’ve spent the past couple days at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans. This was a bucket list item for both of us and was supposed to be a stroll through a period of U.S. history that both of us could relate to, me because of my dad’s role as a Navy pilot in World War II, and Wendy’s because of her dad’s role as a B-17 pilot. Easy-peasy, connect with our parents’ era, see some exhibits, maybe see a 1940s musical show, and wait for Robert and family to show up in a couple days.

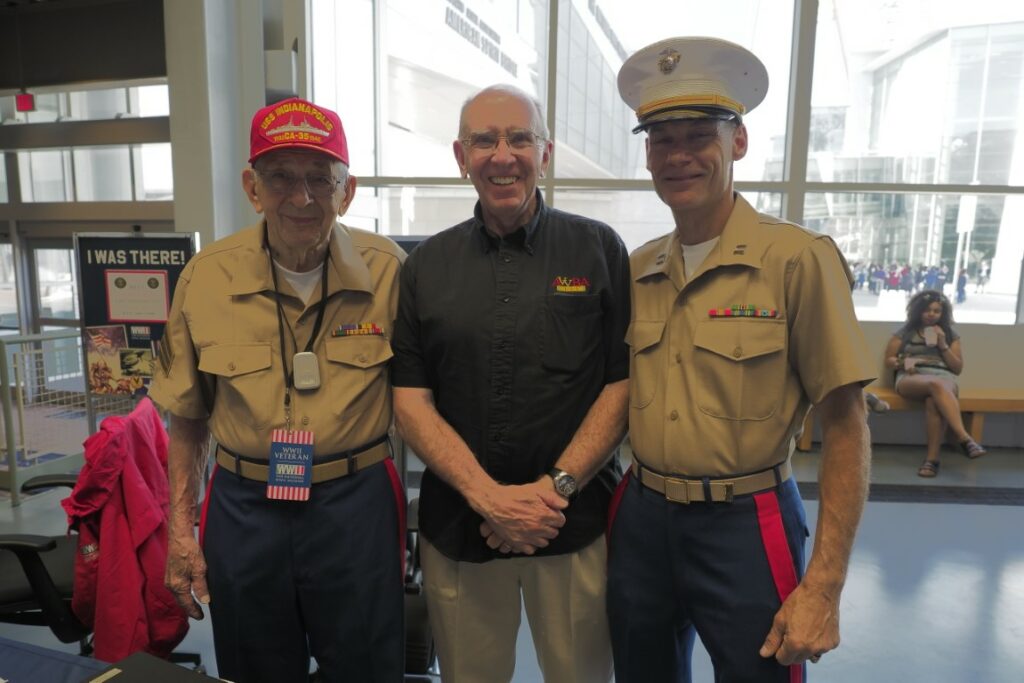

Things started off on a particularly high note. We had the honor of meeting the last surviving crewman from the U.S.S. Indianapolis, Sgt (fmr) Edgar Harrell, and his escort, Marine Capt (fmr) Donald Montefusco, and got to spend an hour chatting with them about those fateful days in 1945.

Then it was off to the first exhibit: the “Arsenal of Democracy,” describing how America geared up for the war effort. Mussolini mocked America, saying that all we could do was to make refrigerators. Well, Benito baby, as Eisenhower said, there is no force on earth like that of a democracy enraged, and it’s a surprisingly small step from a refrigerator to a bomber, and when America created a “war production board” to oversee conversion from consumer goods to war materiel, Mussolini and his Axis cronies learned first-hand exactly what America’s “refrigerator” factories could do: 108,000 tanks; 97,000 bombers; 100,000 fighters; 24 aircraft carriers; 324 destroyers; and 100 billion (that’s billion, with a “b”) bullets. Add to that 15 million men and women in the armed forces. Oh, and in our spare time, we developed the atomic bomb to vaporize the little Axis creeps in the Orient. So far with the museum, we’re pretty good, so with that exhibit done, we were off to the D-Day exhibit.

At this point, though, the nature of our museum experience changed dramatically. The stunning might of the American response occurs in the context of human carnage of an unimaginably horrific scale. The museum experience begins with a film, narrated by Tom Hanks, that recounts the death tally, country-by-country, as a result of the war, for a total of 65 million people dead. And in every museum exhibit, the human cost of this war is clearly and graphically displayed, often in gruesome photographs, videos, and statistics. Over 400,000 Americans died responding to the evil of the Axis onslaught, and the museum does not downplay that terrible cost.

But the museum’s message is not just about the horrors of World War II, but also the heroics of it all. Indeed, in many ways, the museum is more about the unspeakable heroism of ordinary Americans than anything else. As Stephen Ambrose once made clear, at the start of World War II, it was far from clear that a bunch of farmers, teachers, policemen, and clerks could take up arms and successfully overcome an army of battle-hardened professional soldiers. These weren’t guys who were trained to fight. They were just ordinary people who responded when their country called and resolved to do their best. And somehow, out of the ordinary humanity of decent people, there arose the most powerful fighting force the world has ever seen. Throughout the museum, there are the stories of these ordinary guys doing the most daring, selfless acts of bravery one can imagine. And they’re largely not anyone special; they’re just guys doing their job. Millions of them. Over and over and over. Many times, the stories were so overwhelming it was, for me, actually hard to breathe.

We started off with the hall dedicated to D-Day. When the museum first opened in 2000, it was known as the National D-Day Museum, and it was not until 2003 that Congress declared the concept should be expanded to a National World War II Museum. It is the nature of the way Wendy and I travel that we read every display, listen to every audio, and watch every video. As a result, it took us fully five hours to work our way through the D-Day experience.

And so it went, exhibit-by-exhibit, through the entire progress leading up to, during, and in the weeks following June 6, 1944. Even that event, though, is presented in a stark and foreboding context: on that fateful date, while Americans had seen some victories in expelling the Germans from North Africa, and were moving mile-by-mile up through Italy, and had some victories in the Pacific, the entire world, save for a few small areas, was overwhelmingly in the grip of dictatorships. Knowing how this all ends, it’s easy to forget what we were up against, and to forget that the end was never certain, a point that the museum makes clear throughout.

The next day we returned and, after a seeing a couple smaller exhibits, it was off to one of the newly added halls, “The Road to Berlin.” Same deal: one display after another of the stark combination of horror and heroism.

By the end of our experience in the Road to Berlin, we were pretty much exhausted. There was only an hour left before the museum closed, and we hadn’t even started “The Road to Tokyo,” the battle for the Pacific. But we couldn’t. We were too emotionally drained and didn’t have enough time to see the exhibit in our way anyway. So we’ve saved it for another day.

After all of this, one thought kept coming back to both of us. Could America ever do something like this again? Is there enough dedication to our country, as a country, that millions of men would sign up motivated only by a sense of national duty? Do the citizens of America have the character to put their lives on the line to save others? Are we physically and mentally capable of prolonged periods of deprivation and misery to sustain this kind of effort? We don’t know. Maybe. One hopes so. But the museum experience was a glimpse into an era where America was all that and more. And we’re glad we spent a couple days here. We’ll be back.