This post will address our experiences at the Dinosaur National Monument in Utah and Colorado. Eventually. But first, a short foray into the intricacies of the Surface Transportation Assistance Act of 1982 (STAA). That act, among other things, established the “National Network” of roads that are suitable for large trucks. All of the interstate highways are included, as are numerous federal, state, and even local roads that can be safely traveled by long, tall, wide, and heavy trucks. If one buys a road atlas designed for use by truckers, these STAA routes are all highlighted in orange.

Over the years of traveling with various RVs, we’ve learned that the best way to avoid a white-knuckle drive down some RV-eating state or county byway is to stick to the STAA (orange) routes. After all, if it’s good enough for a big 18-wheeler, it ought to be OK for us.

And sticking to orange routes has served us well. Until July 29, the day we took Colorado Route 139 from Loma northward to Rangley, a distance of approximately 70 miles, up and over Douglas Pass (8268 feet). CO-139 is an orange route, so it should have been fine. I got a little concerned when previewing the route, though. Our mountain driving guide noted that the CO-139 northbound assent to Douglas Pass has “6 miles of 6-8% grade with a 25 mph speed limit and numerous 15 mph switchbacks.” Bad enough, but then there’s also this: “About 2-1/2 miles from the summit there’s an 1/8-mile segment of 10-12% grade.” Actually, that section has a road sign that says “14% grade” and the grade occurs in a hairpin turn with a posted speed limit of 10 mph. What the mountain driving guide didn’t reveal, but we quickly discovered, is that in addition to the grades, Route 139’s pavement is in terrible condition, with giant potholes and pavement patches done by poorly trained gorillas, and with essentially none, nada, zippity-doo-dah shoulders. Or, more accurately, the edge of the “pavement” consists of foot-deep ruts that would rip the wheels and axles off of a trailer. And once over the pass, it’s “3 miles of steady 7-8% grades with numerous 20, 25, and 30 mph curves.”

Needless to say, not a fun drive. We stopped once to let the transmission cool down. The transmission temperature briefly hit 235-degrees, which is definitely overheating (although the gauge never hit the yellow line). And while stopped, we learned that the brutal jarring of the trailer had caused one of the window shades to fall off and most of the kitchen contents to be strewn around the cupboards.

Anyway, we made it. I think. We’ll see whether the transmission survived as we continue the trip.

Back to the story. So what of Dinosaur National Monument? The “quarry exhibit” just north of Jensen, Utah, is amazing.

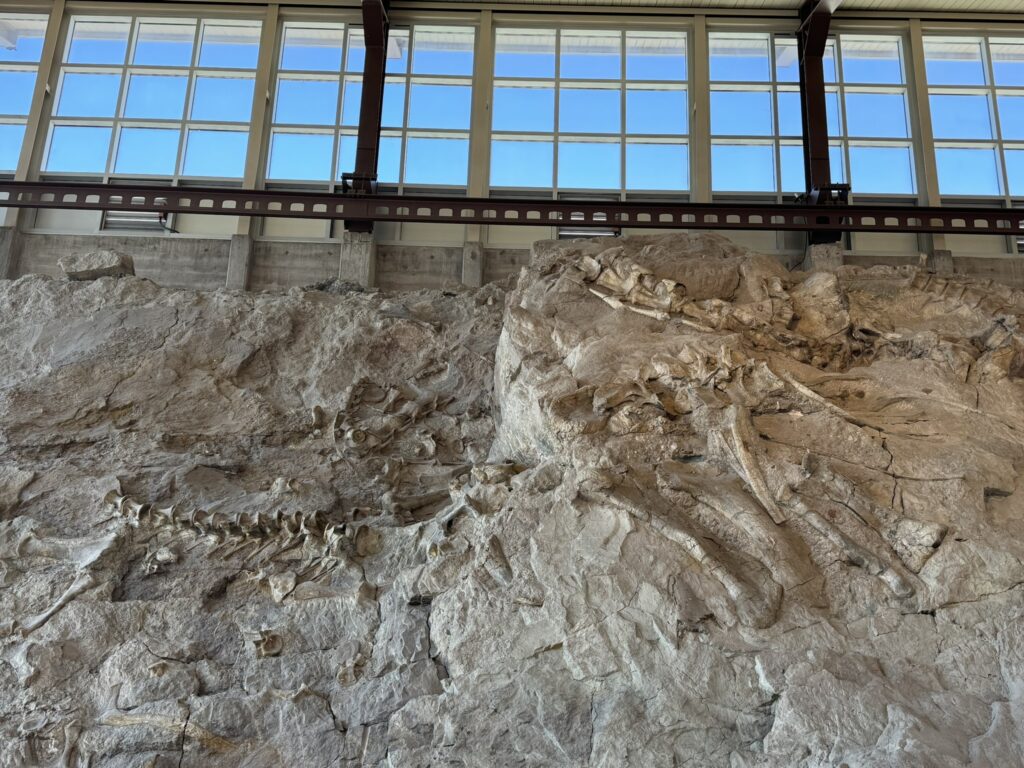

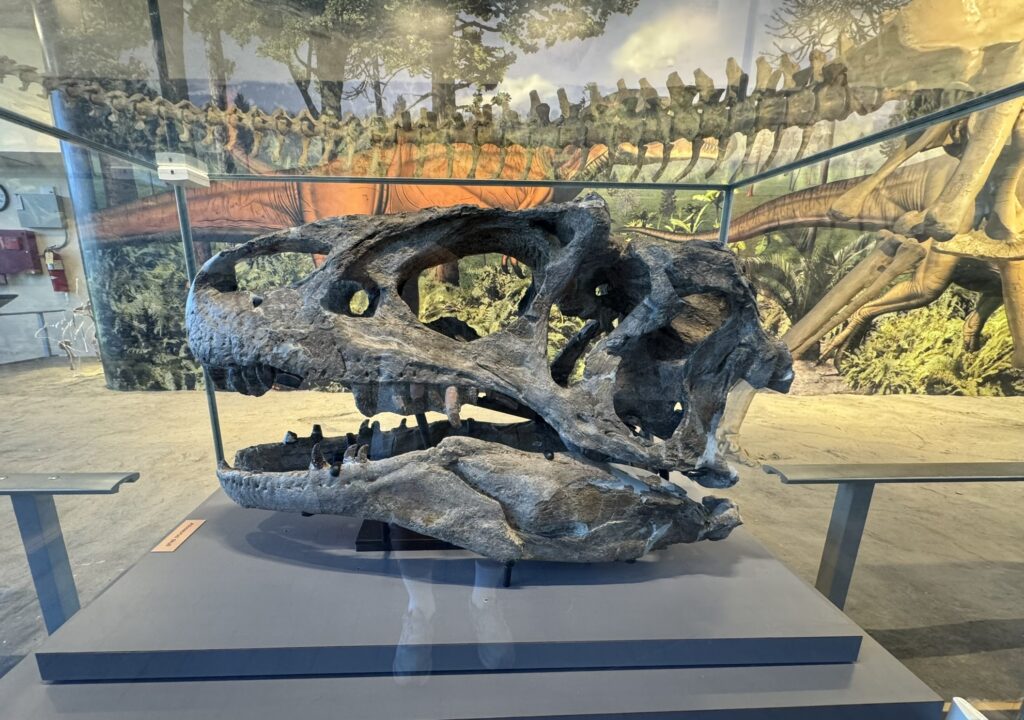

In 1909, Earl Douglas, a paleontologist from the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, traveled to southwest Utah in search of dinosaur fossils. The area had previously received a geological survey, so he thought the exposed layers might be a productive area. He never could have imagined what he saw. As we walked around, he glanced up at an exposed wall of a gulch and there, in full view to the naked eye, was a nearly complete, perfectly exposed section of an Apatosaurus tail! As he started to scrape away the soft soil, he found even more bones. Over the course of a dozen years, his crew eventually excavated over 700,000 tons (!) of materials. In fact, his team obtained so many fossilized skeletons that the Carnegie Museum decided enough was enough and relinquished its claim to the quarry.

But here’s where our country’s public land policies are at their best. When work at the quarry stopped, there were still hundreds of bones visible on the quarry face. Douglas, in conjunction with the Smithsonian Museum and others, decided that this was such an amazing sight that the American public had to be given the chance to see it. So the National Park Service built a building over the quarry and opened it to the public. That is now the Dinosaur National Monument “Quarry Exhibit.”

Besides the quarry wall, the museum has dozens of exhibits and displays. But the point is this. A paleontology find like this quarry, off in the middle of nowhere, and fully understandable only by experts, could have remained something restricted to scientists and visible only to the public in textbooks and PBS specials. Instead, we built a museum over it and opened it up to the public. What a great country.

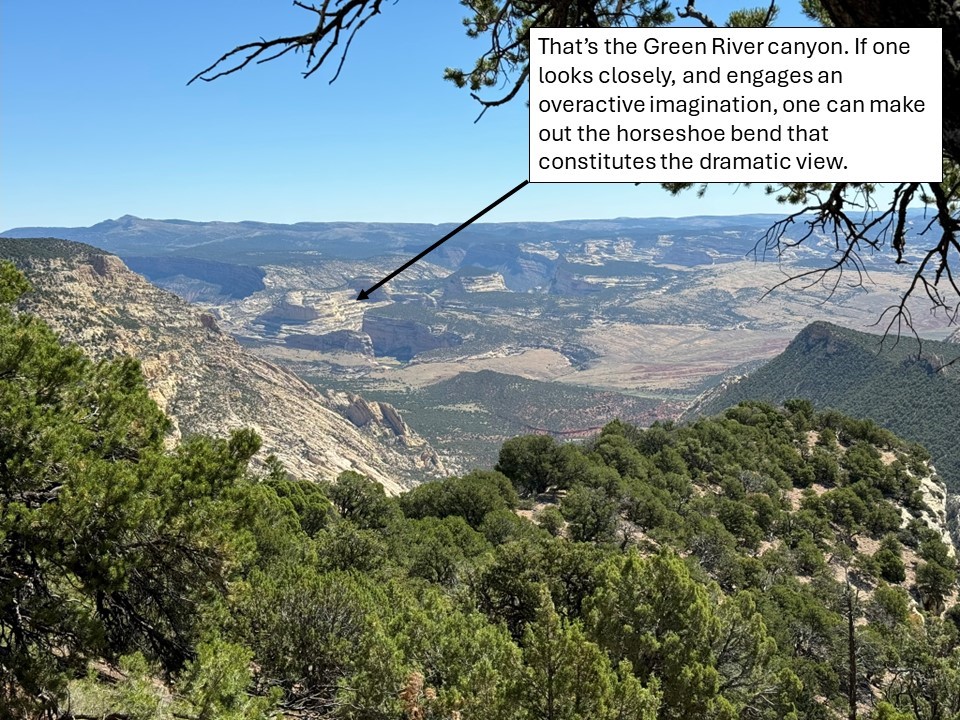

The other half of Dinosaur National Monument occurs north of Dinosaur (aptly enough), Colorado. It was reported to be 31 miles of a scenic drive, culminating in a dramatic overlook of the Green River canyon. Um, no. The 31 miles was actually just a drive through high plains ranch land. Pretty enough, in its own way, but certainly not a “scenic drive.” And the dramatic view of Green River canyon was, well, distant and barely visible.

So, bottom line, the Colorado side of Dinosaur National Monument wasn’t really worth it and isn’t on our list of recommended stops. The Quarry Exhibit is a definite yes; the Colorado side is a definite meh.

Next we have a couple days of drive-days up to Flathead Lake State Park in Montana. Further reports to follow.