In the annals of American history, there are events that mark breaks in the trajectory. For many of us, the assassination of President Kennedy was one. Something spun out of control in our history at that point, launching the sixties, and setting us on a course that made us a different country than we were previously destined to be. One of my favorite books, Coming Apart by Charles Murray, shows how every aspect of our country’s founding values (in terms of religion, marriage, hard work, honesty, and so on) started to change for the worse at that point. For that reason, one destination on my bucket list is Dealey Plaza, just to see the physical place where the event occurred that changed us forever.

In the nineteenth century, one can make the point that a similar breakpoint occurred with the Battle of Little Big Horn. As Stephen Ambrose made clear in Custer and Crazy Horse (which I read especially for this trip), America was on a cultural collision course with native Americans. On the one hand was an industrious and industrial, productivity-minded, land-owning, free enterprise culture, undergoing an explosive growth in population, and on the other was a primitive culture that appeared to Americans as indolent and backwards. What was to become of the Great Plains, for example? Use them for farmland and ranches to feed a growing population, building wealth for future generations in the process (the American imperative), or leave them unused as nothing but rangeland for wandering buffalo (the native American alternative)?

The clash kept recurring, with a result that one “arrangement” after another would be made between American settlers and native populations, with the arrangements not working out very well for either side, and with both sides (not just the Americans, in my view) repeatedly violating the agreed-upon terms. Something eventually would have to give. My suspicion (which I admit may not stand up to scrutiny by knowledgeable historians) is that both sides knew the process was futile: despite all of the treaties, the various peace delegations, splits in factions on both sides, everyone probably knew that one side was going to win and one side was going to lose. Ultimately, there would never be a middle ground.

In that context, on June 25, 1876, a force of maybe 2000 Sioux and Cheyenne Indians, led by Sitting Bull as the diplomatic leader and Crazy Horse as military leader, encountered the 7th Cavalry Regiment under the command of Lt. Col. (brevet Major General) George Armstrong Custer. The rest, as they say, is history. When word of Custer’s defeat reached the East, ironically in July 1876, right at the moment America was celebrating its centennial, relishing it past successes and giddy over its future prospects, the fact that Indians had defeated one of America’s most celebrated heroes was more than the country could stand. One can almost hear a collective response, “OK. That’s it. Enough is enough. Let’s put an end to this once and for all.” As a result of that battle, large military forces were sent west, and within a few years Crazy Horse was dead, Sitting Bull had surrendered, and the west was opened for America’s “Manifest Destiny.” It reminds me of Pearl Harbor. In a way, the enemy may have “won,” but that hollow victory unleashed forces that would leave the “victor” utterly destroyed.

So, here we are in the very place where that shift in the historical trajectory occurred. And besides its historical significance, it’s also a military memorial, a national cemetery, a place where American soldiers fought and died. In all ways, it is for me a place that is both dramatic and holy.

Atop “Last Stand Hill,” looking down towards the Visitor Center. About 5 miles to the south were Reno and Benteen. Through a massive program of GPS mapping and archeology, the place where each soldier fell is relatively well known and is marked by a headstone. Some of the headstones bear names, but most just say, “A soldier of the 7th Cavalry fell here.” The national cemetery is visible just past the Visitor’s Center.

The ravine in which Calhoun’s forces were trying to move to link up with Custer. It’s not really clear from this photograph, but one can see how Calhoun’s troops were using classic fire-and-maneuver tactics, with a series of headstones marking each place where they stopped to provide fire and were overwhelmed. All of Calhoun’s forces were killed.

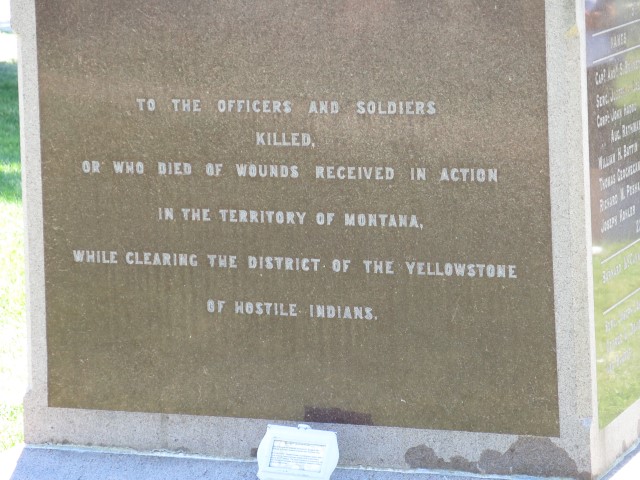

The memorial erected atop Last Stand Hill, I believe in 1881. It marked the place of a mass grave, commemorating the place where 249 soldiers were buried. Some of the bodies were later relocated. Custer is now buried at West Point.

One final thought: Both Wendy and I were a little nervous about seeing the National Battlefield Monument. Our tour guide was a Crow Indian, there is the recent (2003) “Indian Memorial” at the monument, and as one would expect in these times, much of the narrative here extolled the virtues of native American culture. But overall, our fears were unwarranted and things were just fine. The presentations and displays very much honored the American soldiers and, although the native American perspective was included, it did so without in any way diminishing the bravery and sacrifice of the officers and men of the 7th Cavalry.

And one other thing occurred to us both. There are times in history when both sides are right, where both sides are fighting for something noble. To my mind, as I listened to the presentations and pondered the significance of this battle, that was true here. Whatever the deficiencies of the Indian’s “traditional way of life,” and why I think clinging to the traditional ways was not a good choice, every culture has a right to decide for itself how it wants to live, and an insistence on the right of self-determination is a noble ambition. Here, I think, both sides are worthy of honor, and the Monument does a good job of doing that.

Definitely a good stop.

So, that’s about it for the special stops on our way out west. We now have three days of pedal-to-the-metal travel (which means creeping along at 60 miles per hour for us old people) before we arrive at Robert’s. We’ll post some concluding thoughts when we get there.